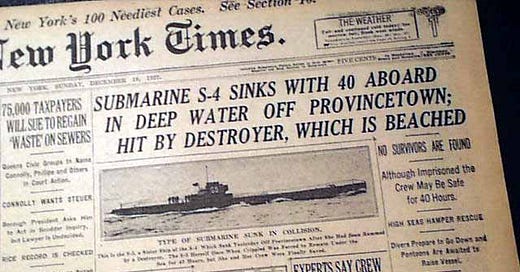

Cape Cod’s most horrifying maritime disaster, on the anniversary

Six haunting knocks on the hull of a submarine; tragedy foreshadowed in a poem by one who died

The vessel didn’t have a real name. It wasn’t even a boat.

Yet this was the most infamous, tragic wreck of the 20th century in Cape Cod waters — 40 men dead off Provincetown, leaving a generations-long wake of bitter feelings about the way the Navy botched the rescue.

Every mid-December for decades, the Church of St. Mary of the Harbor in Provincetown would overflow with a memorial service remembering the moment, the dead. A wooden cross made from timbers of wrecked ships, dedicated in 1937 (10 years after the sinking), still stands in the courtyard, though few people now understand its significance.

This wreck was caused by human error, not storm. This wreck haunted the nation, changed safety and rescue procedures in the United States Navy, and reverberated through Cape Cod’s consciousness.

Who could forget six eerie knocks on a sunken hull revealing that six men had survived the initial accident, suffocating to death days later?

They were on a submarine:

The S-4.

The S-4 belonged to an early generation, 231 feet long, 90 ton, crew of 40. After refitting, it was sent to Provincetown for deep-water trials. Wood End was a good place; the bottom drops quickly, close to shore. On December 17, 1927, the S-4 was put through paces.

The Paulding, a 263-foot-long Navy destroyer, had been converted for different Coast Guard duty; chasing rumrunners during Prohibition. Cape waters were teeming with small boats full of bootleg booze, but on December 17 the Paulding found none, and as weather worsened rounded the tip of Provincetown for the harbor, making 18 knots.

Southwest of Wood End, the S-4 was breaking the surface, showing enough periscope to be seen by a lookout at the Wood End Coast Guard station. Perhaps bad surf and a rising northwest wind obscured the view, perhaps the Paulding was moving too swiftly or wasn’t paying attention; destroyer collided with sub at 3:37 on a Saturday afternoon.

The Paulding drove a hole into the starboard side of the S-4, forward of the conning tower, raking over the top. Within five minutes the sub sank in more than 100 feet of water.

The destroyer sent an immediate message:

“Rammed and sunk unknown submarine off Wood End Provincetown.”

The Paulding limped for harbor, and beached.

A Coast Guard boatswain fought through worsening surf, trying to locate the downed sub and hold position. He found it with a grapnel but lost it and had to scour again. Meanwhile, the only salvage ship the United States Navy had in the Atlantic, the Falcon, was steaming from New London. Divers were on their way from Newport. Six pontoons — buoyant structures that might draw the sub to the surface — were coming by tugs from New York.

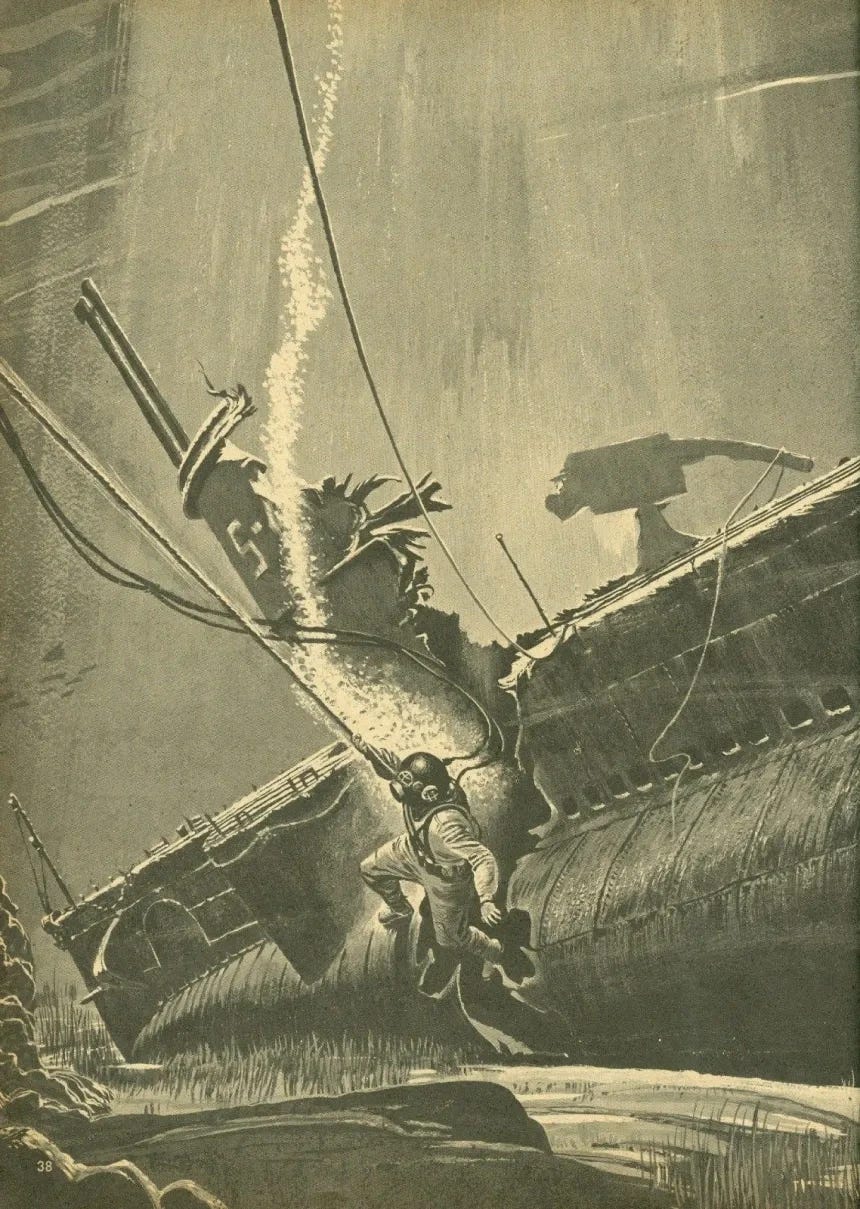

The Falcon arrived at 7 am Sunday morning. The sub had been lost again; it took almost four more hours of sweeping the bottom to make contact. Finally diver Tom Eadie prepared to go down a grappling line.

His lead shoes landed on the hull with a thud. From within came an answering signal in the forward section — six taps, six alive. Aft, no answer; 34 men must have died.

Weather was deteriorating. Rescuers had a decision:

The S-4 was outfitted with two emergency connections to the outside world. One was an air line for crew compartments. The second was a line to the ballast tanks.

Should they try to re-float the sub through ballast, or force oxygen into the compartment where men were trapped?

They decided to send air into the ruptured ballast tanks — pumping oxygen into the Atlantic Ocean.

When Navy crews realized their error, they sent a second diver, Frederic “Whitey” Michaels, down to try to hook up another line. He tangled in debris, became trapped for almost three hours while the first exhausted diver, Eadie, went back down to free him. Michaels was rescued, but his quick ascent gave him “the bends.” The Falcon broke off rescue attempts Monday morning and raced to Boston to try to save Michaels’ life.

Why send the Falcon? Why not another vessel and keep working to salvage?

It was another decision that proved futile, even to save one life; Michaels died in a Boston hospital days later.

Meanwhile, communication had been established with men still breathing within the hull. The Navy used an oscillator to amplify Morse code the men were tapping on the hull, using a wrench.

Twenty-four hours after the accident, the following exchange:

“Are you alive?” (In retrospect, what the hell kind of question was that?)

“Yes, six of us are alive here.”

“Everything possible is being done to help you.”

“The air is very bad in here, please hurry.”

Names of the men were tapped; Fitch, Short, Crabb, Pelnar, Snizek, Stevens. Millions across the country prayed in simultaneous silence on the night of December 19. Relatives sent Morse code prayers.

“We understand,” they tapped back. Then an ominous message: “Oxygen bottle empty. Can you send down a couple?”

Local fishermen offered help. Could the fleet could attach lines and, together, haul the sub to shore?

No, said the Navy.

Without more air, the men would suffocate before the storm abated. To make matters worse, if possible, the line locating the sub broke again.

Provincetown draggermen offered to drop their dredges, claw the bottom until they knocked against the sub. Again, the Navy turned them down. The salvage ship took more hours to find the hull.

When divers finally connected a line Wednesday afternoon, pumping oxygen into the compartment where six men had lasted for several days, no lungs took it in. No Morse code.

The Navy wanted to leave the sub on the bottom until spring, but Provincetown (and the nation) was incensed. A salvage began. Still, it took three months before the S-4 was re-floated, dragged to Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston. One by one, bodies were removed. Even the wrench was recovered.

A court of inquiry convened at the order of President Coolidge. The court blamed commanders of both the sub and destroyer plus the rear admiral in charge of rescue operations. But when the report emerged from the Secretary of the Navy, it was sanitized. Only one man was blamed for the accident, the only man who could not defend himself; the dead commander of the S-4.

The sub was repaired, recommissioned 10 months later, used for training. New designs for salvage pontoons were more rugged, greater lift, easier to deploy. Because divers had been hampered by freezing moisture on breathing apparatus, improved techniques for working in cold water were developed.

The S-4 served until May 15, 1936, when the Navy ended its time in the most appropriate manner — sinking in deep water.

The tragedy focused hard feelings about government attitudes toward the fishing fleet. But it was human drama, Morse code, wonder about what it must have been like to be trapped in that compartment, that pierced the national consciousness.

A voice from the dead added to that pathos. Soon after the accident, a poem written by the radioman aboard the S-4, Walter Bishop, among the 34 to die quickly, was reprinted. Here are eight of 12 quatrains Bishop wrote, part of what he called, “Poem of the S-4”:

Poem of the S-4

In the cankerous mind of the devil

There festered a fiendish scheme

He called his cohorts around him

And designed the submarine.

They planned and plotted to do their worse

In perfecting this awful thing

And since completing their hideous work

Are awaiting what evil it will bring.

…

Yes, daily we make a risky dive

While Uncle Sam with his brimming cup

Bets us a dollar, while we’re alive

A dollar to nothing we don’t come up.

We’re bottled up, just like a trap

With nothing in between

The sea and death, but a metal cap

Like the lid on a soup tureen.

We get $5.00 bonus

They call it extra pay

But it always goes to dungarees

That the acid eats away.

The best blood in the service

You’ll find on the old pig boat

For it takes more than a common mind

To sink and still to float.

…

There’s a sort of fascination

Attends this job of ours

That could only be duplicated

By a rocket trip to Mars.

We cuss and mutter “never again”

Until we get paid off

But the blamed old life will drag us back

No matter how we scoff.

Haven’t subscribed yet? With all due respect, why not? Make it possible to see a Voice and support good reporting, strong perspectives, unique Cape Cod takes every week. All that for far less than a cup of coffee.

So please, subscribe:

https://sethrolbein.substack.com/welcome

And if you are into Instagram, want to see some additional material, maybe share the work, here you go:

I.m a commercial diver myself, and if i am correct, Michaels should have had an accend time of at least 9 hours to decompress. On different depths while ascending. If he,s been there for 3 hours on 100 feet. Would be interesting to know if he was put in a decompression chamber. Tragic for all involved.

Great piece, Seth. Cheers!