How skinny ‘woodlots’ became building lots

Cape Cod’s first subdivisions were parcels only a few feet wide

They were called “woodlots,” because their only value derived from firewood or building materials that could be cut out of them.

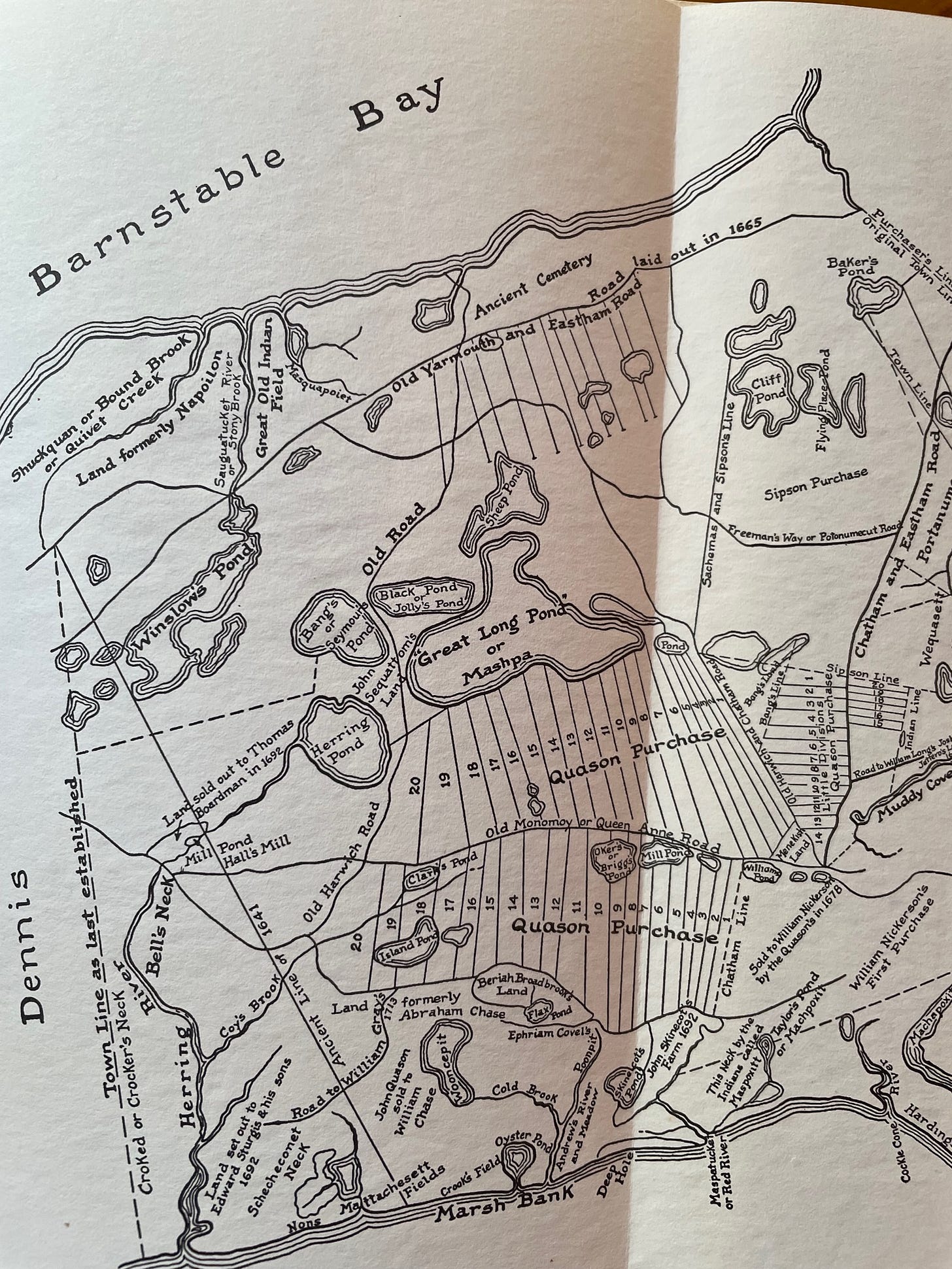

They also were called “shoestring lots”; each parcel needed just a little frontage on a road to get the wood out, maybe only wide enough for a wagon. But everyone wanted as many trees as possible, so the lots were long as possible.

Woodlots are “engrained” in Cape Cod history — our first subdivisions. In every town, except maybe Provincetown, they played a key quiet role in lives and economies.

Moments came when they no longer were useful or needed, their presence a nuisance, long thorns in the sides of tax collectors. Then came the next moments, when those stringy subdivisions created opportunity to turn much of the Cape’s interior into modern versions of subdivisions; suburbia.

In Colonial days, with no central heat and multiple open hearths, people burned huge stacks of wood year-round; Goodman Hallet, who lived in a modest 17th-century Cape home, estimated that he burned 40 cord a year, probably typical. Meanwhile, businesses like the Sandwich Glass Factory consumed mountains of cordwood keeping their furnaces hot enough to melt sand, while hardwood was clearcut for boats and home construction, cedar for split-rail fencing, the list goes on.

Speaking of Sandwich, it used to be that if you bought a handsome dwelling along what is now called Route 6A, at the closing you often received something extra with your deed, a box wrapped in a nice red ribbon.

What was inside? Deeds to woodlots that went with your property.

Why was it done this way? So the town wouldn’t know you owned those too, and wouldn’t tax you.

Those deeds were sometimes imprecise, though not for lack of competence; people in those days could survey down a stairway if required. Again, vagueness diminished authority to hold you accountable. The tax collector would need more evidence.

Woodlots typically were 10, 20, even 50 acres. Sometimes they became ridiculously exaggerated; in Bourne, there were woodlots 150 feet wide, butted up against each other on a cartway, and three miles long.

Quite a shoestring.

Because their value had only to do with trees, as soon as lots were cleared they became worthless for 20 or 30 years. People often treated them the way they treat anything worthless – forget about it, certainly don’t pay taxes on it.

Deeds moldered in drawers, eventually discarded at a spring cleaning. More and more woodlots became “owners unknown,” taken by towns for taxes due. As recently as the 1950s, Brewster didn’t bother to charge taxes on cleared woodlots even if the owners were known; it was worthless.

They couldn’t be used for anything, not enough width to build something wider than a stick. Even if you could, only the first chunk had frontage on a road, so there was no access to the back 40 if you wanted to subdivide.

But if those shoestrings could be tied together, opportunity materialized. Come the growing popularity of Cape Cod in the 1960s, rising demand for second homes, that’s exactly what happened.

Sharp land speculators, mostly old Cape Codders, realized what they needed to do to turn woodlots into building lots:

Define the bounds and trace sketchy ownership as well as possible, maybe pay some back taxes, then present the findings to the Massachusetts Land Court to make a claim for ownership. Distant relatives of old owners (perhaps mentioned in a long-forgotten will) were contacted (if not fully informed), then bought out. What looked from afar like an unexpected windfall looked locally like very short money on a good bet.

Land Court often allowed the claims, removing clouds of title over bundled woodlots, clearing skies for new owners. The boom was on.

Driving through the Cape’s suburban interior, it’s certain that much of that land once was that thing called woodlots. Now their name?

Buildable lots.

Haven’t subscribed yet? To keep seeing a Voice (a cool trick), please support this local expression:

https://sethrolbein.substack.com/welcome

I bought one off route 137 in Brewster some years ago. It measured 100 feet wide and 12 hundred feet deep. Twelve hundred feet is almost a quarter of a mile. Bruce MacGregor