Out of sight, out of mind: The Foul Area

In search of truth about dumping radioactive and hazardous waste off our coast

Back in 1990 I started hearing scary things about what might be lurking on the sea floor between here and Gloucester, due east of Boston.

For anything ocean-related, my first stop always was to Louie Rivers, Provincetown’s great fishing captain.

“Louie, you ever heard of a fisherman from Gloucester named Salvatore LoGrasso?” I asked. “Everyone calls him Sammy.”

“No,” he yelled, offloading whiting at the pier. As usual his elderly father and retired fisherman Jack, who still spoke Portuguese decades after coming here, had come down to watch (and take a fish or two).

“Papa,” Louie called, “você sabe uma família de pescadores de Gloucester chamado LoGrasso?”

(Daddy, do you know a fishing family from Gloucester named LoGrasso?)

“Italian,” dismissed Jack.

Louie’s wife Marjorie, a Gloucester girl, knew the LoGrassos from before she let this Provincetown Portagee lure her to the tip of the Cape. Old man LoGrasso came from Sicily, not too different than Jack coming from Portugal. Sammy had been fishing for more than 30 years, again not too different from Louie.

“Did you hear what happened to him?” I asked.

“Not a word.”

Sammy’s boat was the Italia, a bigger version of Louie’s Miss Sandy, 64 feet, a dragger that scoured the bottom with a big-bellied net pulling up everything in its wake. One day Sammy and his boy Marco were doing just that south of Gloucester. But this time, as the net bellied up and hundreds of fish came flopping onto the deck, something else was in there too:

Four drums, 55-gallon barrels, two plastic and two steel.

“Fishermen around here, we get them all the time,” Sammy told me, his English brusque and accented, eyes averted like he felt shame. “So what do we do? We push’em back in the water. What else you gonna do?”

But this time one of the barrels broke open on deck and began leaking a bright yellow liquid, then other colors. Marco was by the bow and slapped something over his mouth and nose right away, but Sammy was with the net and inhaled. He became confused and dizzy, couldn’t keep his balance. Marco had no choice but call the Coast Guard, who airlifted his father off the boat and ordered the Italia into quarantine.

The nightmare had begun.

The liquid was a toxic brew of corrosive acids and industrial waste with names like phosphorous pentoxide, xylene, dioxane, chromic acid, and ether. Wood on deck was contaminated. They had to destroy nets, fish, clothes. It took two weeks to get the Italia out of quarantine.

Sammy checked out of the hospital and thought he’d be fine, but kept getting dizzy. That went on for months even though his doctor was giving him vertigo medicine. He tried to fish again, lost his balance, fell, cut himself.

Without income, under-insured, they couldn’t make the boat’s mortgage payments. Ten months after the encounter, the Italia was seized and put up for auction.

No takers.

“I swear to you, I was miles away from the Foul Area,” said Sammy, putting a fist by his heart, then crossing himself. “I don’t go in there, it’s not worth it. But the barrels, they everywhere anyway.”

“The Foul Area?” I asked.

“That’s what ruined me,” said Sammy.

The Foul Area.

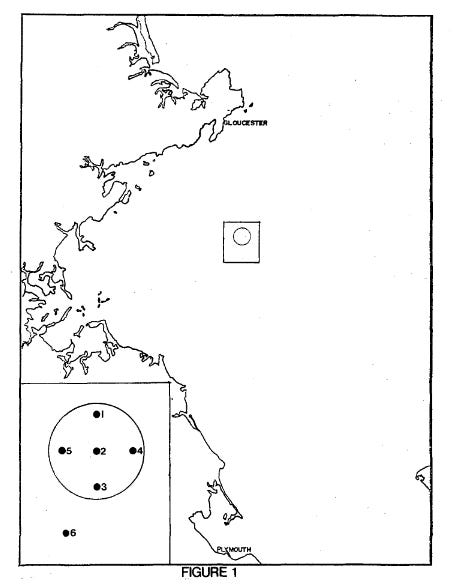

You can still see it on charts and maps, less than 20 miles east of Boston Harbor, northwest of Provincetown’s tip. Beginning at least in the 1940s, when people had crap they needed to disappear they loaded it on boats and dumped it there, in water maybe 250 feet deep — close and shallow.

But did they always make it all the way before they dumped?

Of course not.

Did ocean currents, time and tide, fishermen dragging here and there, move stuff around?

Of course.

The bullseye, intended to concentrate pollution and give people warning to stay away, was not much of an eye.

“Maybe in a way I get lucky,” said Sammy, though he didn’t look or act lucky. “Maybe to get sick like this is better than getting radioactive sick.”

“What do you mean?”

“I hear they dumped ‘the radioactive’ out there, same way. At least I didn’t get one of them.”

“Who told you that, Sammy?”

“People just say it.”

After more than a month diving into reports from organizations like the International Atomic Energy Commission, talking to fishermen who didn’t want to talk about pulling up barrels of weird shit, calling environmentalists who didn’t really know much but wanted to sound an alarm because that’s what they do, I found myself on a porch off a bungalow in a subdivision in Hyannis.

An old man was sitting in front of me in a rocking chair, grey crewcut, unshaven, white t-shirt over an expanding belly. His speech was a little blurred, his mouth dribbled a bit, he was hard of hearing and needed a walker, but his brain was intact.

“You’re George C. Perry, aren’t you,” I yelled.

“I am,” he rumbled.

“Did they used to call you ‘The Atomic Garbage Man’?”

“They did.”

“Holy shit, George, I been looking for you and all this time you’re in Hyannis. Could I sit down and talk about what you did?”

“Sure. What the hell they gonna do, put me in jail after all this time? Besides, everything I did was legal.”

(Next: George Perry’s stunning story: “Gangway for the Atomic Garbage Man!”)

Haven’t subscribed yet? With all due respect, why not? Make it possible to see a Voice and support good reporting, strong perspectives, unique Cape Cod takes every week — where else do you see reporting like this?

All that for far less than a cup of coffee.

Here’s a serious question:

If reporting like this is not worth supporting, what is?

Please, subscribe:

https://sethrolbein.substack.com/welcome

And if you are into Instagram, want to see some additional material, maybe share the work, here you go:

Another "wow!" Can't wait for the next installment.

Aside: Over the years I've done a lot of walking, biking, and horseback riding in the woods of Martha's Vineyard. In the earlier years, up to 2000 or so, I saw plenty of dumped garbage (some islanders' resistance to the notion that they had to pay at the town landfills) and several junked vehicles, all of them at least 30 years old. So it doesn't surprise me in the least that people have been dumping hazardous and radioactive waste in the ocean, which is far more vast than the woods of Martha's Vineyard.

I well remember the stories in the paper in tge 1960’s and 1970’s. Busted bombs from Otis and tge target ship, industrial wastes

My father often joked, in sarcastic disgust: “The ocean is the ultimate dump.”

Knowing full well that someday it would come back to haunt us, there’s no way to clean it up. Pollution of the fisheries, swimming…”Ocean Dumping” as it was generally called was what we did. The intention was for it to go over the shelf i.e. off the bank where we don’t fish but rumor was oftentimes it wasn’t. Some said it was better to dump on the George’s Bank because if we ever wanted to clean it up we might want to recover it. Bombs we’re almost certainly always taken to the shelf as no one wanted to drag up one of those. But I think some said they got some in their gear. The dumpers also being fishermen or friends with them…We hung together with Otis and the requirement

I understand that there are nuclear bombs over the shelf. One or two that were so broken and dangerous that was the only idea. Over the road or dismantled on the land was viewed as unsafe. Still today, how could we ever cope with such things?