When Louie fished 250 days a year

Miss Sandy looked rusty, but she was a jewel, as was her captain

Louie Rivers was among the finest men I’ve known, and times spent aboard the Miss Sandy are my best memories on the water.

Our days began before the sun, walking dark Provincetown streets to the pier. This was the 1980s. Young men were ending their adventures as we were starting ours, lounging on benches in front of town hall nicknamed “the meat rack.” Sometimes they would make lewd comments about what they thought was an odd couple, a young long-haired bearded guy alongside a squat older man with arms like thick oak limbs and a rolling gait because his hip hurt from years using his foot to broom fish off the deck.

Louie would just laugh, never taking umbrage. In all our years I never saw him get into an argument or fight, on or off deck or dock, a rare thing among fishermen.

Miss Sandy was tied up at MacMillan Wharf like a patient dog waiting to get off leash. The fleet at that time numbered 35, maybe 40, almost all small draggers. Built in 1978, 58 feet with a steel hull, Miss Sandy was a jewel even if she looked rusty. She was a stern trawler, meaning her net played off the back rather than the side – hydraulics allowed this safer, more balanced method, you didn’t need five or six men hauling hand over hand at the long rail using “Portuguese power.”

You could always find Miss Sandy because Louie lashed a Christmas tree to the top of the mast, his whimsical signature. That and shorts, which he wore in almost all weather because, as he said, he had nice legs.

The boat was named for Louie’s daughter Sandy, who died as a young woman from complications related to asthma. It was one of the few things Louie would not talk about, not even much with Marjorie, who he convinced to move from Gloucester and marry him in 1947, the same year as Provincetown’s first Blessing of the Fleet.

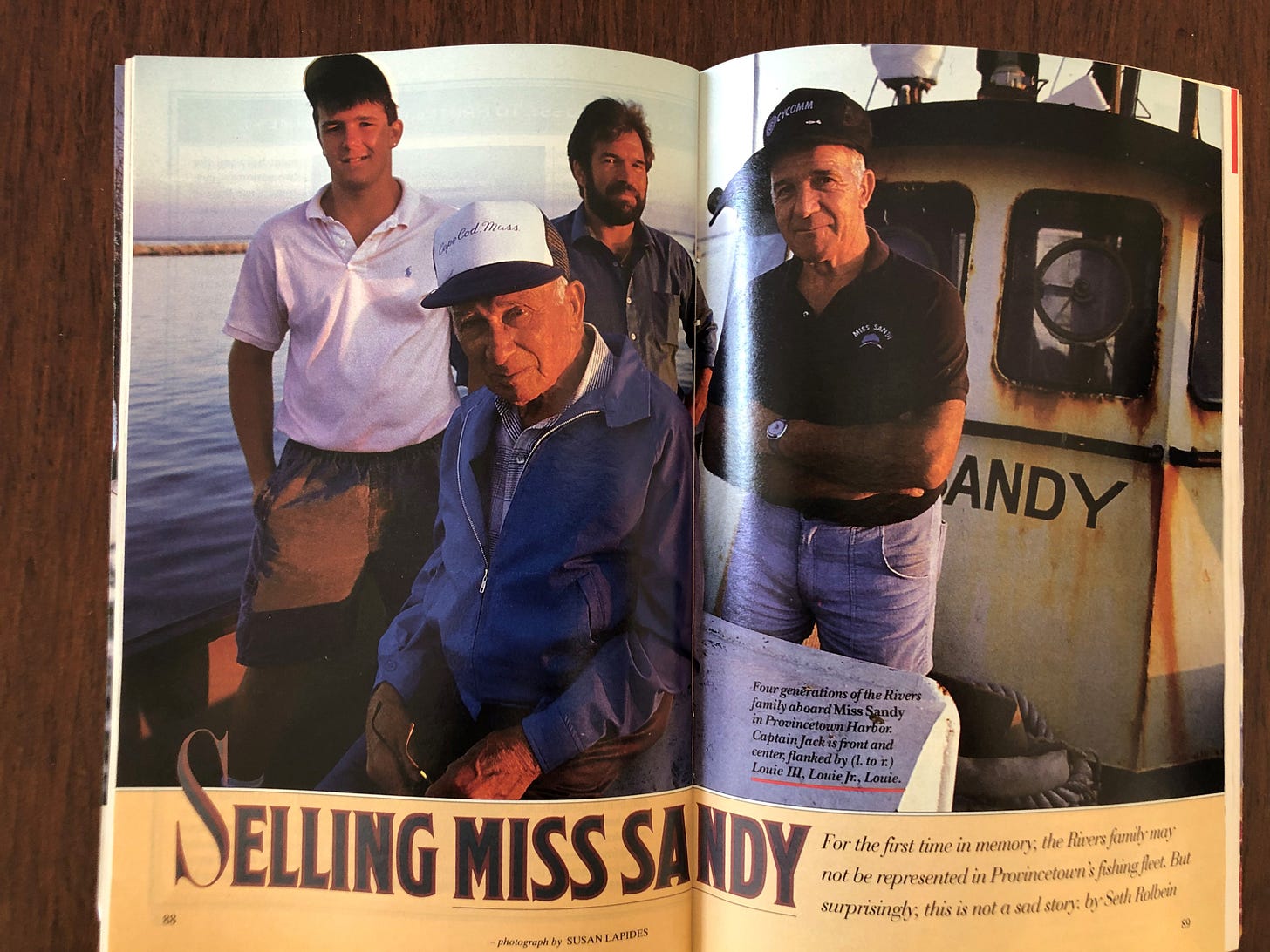

Louie already was fishing with his father Jack, who had debarked at Ellis Island from a Portuguese town called Fuzeta in 1913 and wound up in Provincetown, catching fish and making a family. Jack’s first boat was the Emilia R, a converted rumrunner. In 1990, at 93, Jack led the fishermen’s procession at the Blessing. He never spoke much English, but even in his 90s he often made his way to the pier at the end of the day to accept free fish from an offloading captain.

If the day was nice Louie would announce, “It’s gonna be a corker, Seth!” and then jump on the two-way radio, checking with other captains, rumbling in Portuguese or English as suited the man. He would gesture to a small plaque on the wheelhouse wall which read, “Deus Toma Conta Desto Barco O Capitao E Os Tripulantes,” meaning “God Bless This Boat, the Captain, and the Crew.”

Soon we would clear Wood End and steam into the bay, into sunrise. Louie often fished 200, 250 days a year; whiting was an important stock for him and Provincetown. He would lay down his doors and play out on soft bottom, mud and sand, avoiding rocks and wrecks that would snag and tear the expensive net. He would tow for a couple of hours, then haul back.

The big belly of the net would emerge dripping seawater, bulging with anything and everything in its path. Louie would yank and release the cod end, which held the net closed, and the catch would drop onto the deck where sorting would begin amid much flapping and writhing. All manner of things might show up besides whiting; flounders and gray sole, big fish and babies, lobsters, junk off the bottom, wooden slats or old barrels, busted buckets.

“It’s like a Christmas present,” Louie would joke. “You never know what you’re gonna get until you get it.”

Once the catch was sorted, net played out for the next tow, there was time to talk. These were the moments I cherished, staring toward the horizon, Louie so in tune with boat and net he would make adjustments with one finger on the wheel.

His knowledge of the town matched his knowledge of the bay and Stellwagen Bank, and his intuition about people more than matched his intuition about fish. His human comprehension was honed during one stint away from the water, when he ran a jumping nightspot in the late 1950s and early 1960s called Louie’s Dine and Dance, in Truro.

The sea drew him back, and when I asked why, he offered one of his many wise and humorous perspectives:

“Working in the bar, we had to deal with human nature. Fishing, we have to deal with Mother Nature. And I’ll tell you, I’d much rather deal with Mother Nature, she’s a lot more predictable.”

It pained him that his style of fishing killed a lot of small fish he couldn’t land and sell. They would get crushed in the net, when he kicked or broomed them back into the sea they usually didn’t survive plus the cawing seagulls fed off his every tow. He knew he was robbing from the future, sometimes even resorting to the word “rape.”

He had a theory that small draggers like his, on soft bottom, avoiding rocky ledges and promontories that remained fertile oases for spawning fish, didn’t create the disaster. But bigger, more powerful boats arrived with gear called “rock hoppers” and “street sweepers” that could roll over jagged bottom like trucks with big wheels can pummel and flatten terrain, so those spawning areas were destroyed. That, he believed, made the crash.

Louie had a son, Louie Junior, who fished awhile, who had a son also a Louie, which turned Louie Junior into Louie Middle. But fishing was not in either of their blood the way it was for Jack and the original Louie. Louie Middle became a title surveyor, as much on and about land as you could be. And “Louie Little” turned away from it too.

“When I first decided not to go fishing, I thought grandfather and great-grandfather would be kind of upset,” the youngest Louie told me one night, sitting in his grandfather’s living room. “But they know it’s a lot different for me than it was for them, there’s a lot less fish and a lot more for me to do. So the fishing industry, as far as this family is concerned, is going to die right here. It ain’t getting past me.”

Then he laughed -- and so did his eavesdropping grandfather.

You might think the decision secretly bothered Louie, but no, he was too compassionate. He saw that both son and grandson were happier on land. And when the time came to sell Miss Sandy, he did so full of memories but not regret.

After Marjorie passed, he kept busy going to the Lions Club, driving his buddy Art’s dune buggies, regaling tourists. Unlike his father, he didn’t go to the pier much. But in 2008, when he breathed his last, all of the older Provincetown Portuguese community came to St. Peter’s to celebrate mass, and Louie.

That was the last time I was in the beautiful Catholic church before it burned, gleaming rays through stained glass of St. Peter on the seas filling the hall with gold and blue light. My vantage was good because the family asked me to deliver the eulogy – me, not Portuguese, not from town, not even Catholic.

It was among the great honors of my life.

Haven’t subscribed yet? Here’s how to keep seeing a Voice:

One of your best written stories ever, Seth. Your love of the man shows.

Beautiful story, well written, Seth. Wish I had known the Louie's.