In part one, "Out of Sight, Out of Mind: The Foul Area", we met a fisherman damaged decades ago by an encounter with underwater barrels of hazardous waste. After much investigation, I found the man who likely dumped those barrels, George Perry, living in Hyannis in 1990. He agreed to tell me about his life and times as “The Atomic Garbage Man.”

“What’s your name again?” George asked. “Seth, OK, go inside, ask the missus to find my old scrapbook. She knows where it is, might come in handy.”

His wife looked at me coolly. “No harm I suppose,” she said after awhile. “Let George tell his stories one more time.”

“I offered my body to science,” called George as I sat down next to him. “Anybody want to study me, see how I would deteriorate after handling all that stuff for so long, welcome to it. But nobody took me up on it. Now it’s been 30 years since that ended, and as you can see I’m not dead yet.”

It started in 1947. Born and raised in Brookline, George had been a carpenter like his father. He got interested in scuba diving when a guy on his crew got drunk one day and threw his tools into Boston Harbor. Perry got ahold of a diving suit and tank to go looking for them, and became fascinated by the underwater world he entered.

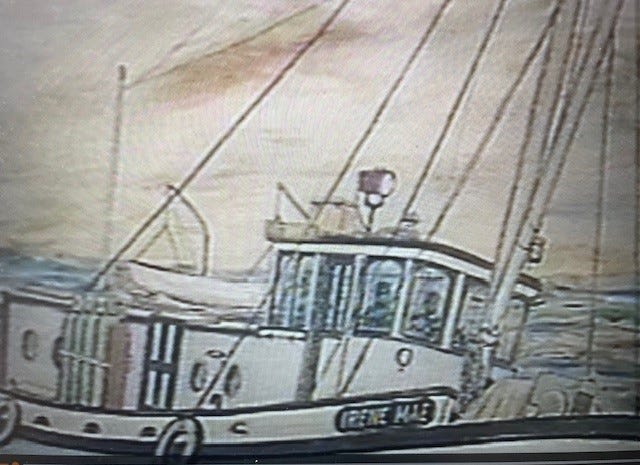

He got his hands on a 65-foot, 1919-vintage boat, the Irene Mae. She was tough and strong enough to get him into marine salvage work, and he was tough and crazy enough to create a reputation for being willing to handle anything anybody brought his way.

“One day this guy showed up on the pier on Northern Avenue … Of course I remember his name, it was John Santangelo,” said George. “He had some stuff he wanted to get rid of, he went to the Boston police and asked them what to do with it. They told him to go find me. So he brought me a load of boxes and barrels — but he wouldn’t tell me what it was.”

George cared less. He loaded it on the Irene Mae and steamed to the Foul Area:

“I charged 50 bucks, hell, it was a nice day and all I had to do was throw it overboard and come back.”

The next time Santangelo showed up, two months later, he was ready to talk about what was in the containers:

Radioactive waste from labs around Boston, mainly MIT, doing work related to the Manhattan Project that created the first atomic bomb — contaminated stuff, clothing and gloves, test tubes, “hot” metals and liquids.

George cared less. Given that attitude, Santangelo figured he’d found a business partner.

They started a company called Crossroads Marine & Salvage, named after “Operations Crossroads,” nuclear weapons tests conducted by the United States government in the Pacific Ocean at Bikini Atoll in 1946. With the Irene Mae, and a silent third partner called the Foul Area, they were in the disposal business.

“I never would have made a living just from ‘the radioactive,’” George told me, rocking on his porch. “I took any stuff no one else would handle — chemicals, poisons, metallic sodium. When that stuff hits the water, it explodes, and I mean a big explosion.

“Hospital refuse, I thought up this technique: I’d put lots of needles and vials and so forth into a 55-gallon drum, tie a 25-pound stick of dynamite to it. Then I’d float the drum 500 feet behind the boat and detonate it.”

Pretty much every hospital around Greater Boston hired him at one time or another, said George.

He invented other techniques too. He’d pour hazardous waste into drums, steam out until he figured he was around the Foul Area — no buoys marked the spot, no modern navigation — and then he’d roll the drums into the water, get out his 30-06 rifle, and shoot holes in them. That way they’d fill with sea water and sink instead of washing ashore.

Sometimes he’d invite Boston cops to come along for target practice and a nice day on the water. Made for good business relationships.

But with “the radioactive,” he took steel drums and lined the bottom with four or five inches of cement, let that harden, then packed material. He sealed the top with more concrete, mainly to make sure they sank.

“About a third of what I dumped was like that,” George rumbled on. His customers were big businesses around Boston; Westinghouse, GE, Raytheon, Polaroid. The Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland once sent up more than 100 concrete vaults by railroad car.

“They were like child-sized coffins,” George remembered.

He dumped them without a clue of what was inside.

Then there was the night he got an emergency call from the Groton, Connecticut naval station:

“They had been working on the inside of a nuclear sub when something went wrong and they contaminated it. I went down there with 75 empty drums on a trailer, filled them all up, brought another trailer back, and filled half of that.”

Overboard it went.

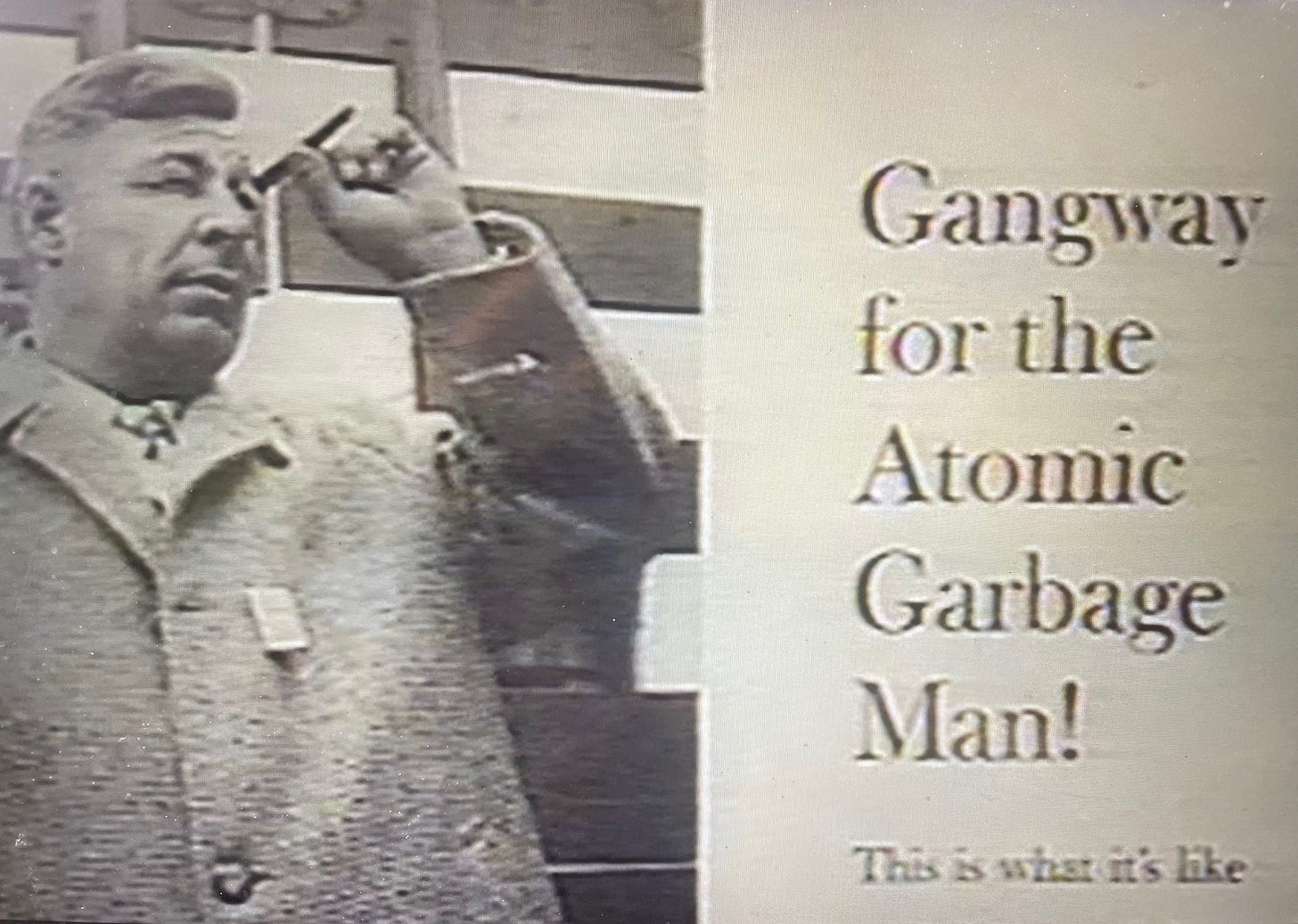

Rocking, reminiscing, George opened the scrapbook in his lap. There he was, young and vital. True, The Man’s Magazine, 1957, headlined “The Man Who Dumps the Atoms.” A Boston newspaper named him and his crew “The Fearless Five.” “Gangway for the Atomic Garbage Man!” announced The Saturday Evening Post in 1958.

As this stunning first-person story unfolded on a porch in Hyannis, here’s one of many things I was thinking:

George couldn’t have been the only person doing this.

(Next: George Perry in context. From Boston Harbor to the mid-Atlantic to the Farallon Islands in the Pacific, radioactive waste dumping spanned oceans, and decades.)

Haven’t subscribed yet? With all due respect, why not? Make it possible to see a Voice and support good reporting, strong perspectives, unique Cape Cod takes every week. All that for far less than a cup of coffee.

Here’s a serious question:

If reporting like this is not worth supporting, what is?

Please, subscribe:

https://sethrolbein.substack.com/welcome

And if you are into Instagram, want to see some additional material, maybe share the work, here you go:

I’m hoping a some point “The Big Cleanup” will be the title of the installment, but I’m doubtful and so sick to my stomach reading about this. Our poor oceans.

896344 Pulitzer-worthy, Seth. So discouraging to read these 2 pieces.