The Texas Towers

We were sure offshore platforms would withstand anything the Atlantic could muster. Instead, disaster and death. Sound ominous? Maybe familiar?

Given all the talk about offshore wind development, new leases approved for massive areas in the Gulf of Maine even as our new President seems intent on “drill baby drill” versus “blow baby blow,” this is a good time to invoke some tragic Cold War history and revisit an idea that once seemed great:

Build massive platforms in the Atlantic Ocean off our coast.

They were called Texas Towers, and we can only hope offshore wind turbines stand up to the Atlantic’s rage and perform a helluva lot better — with fewer lives lost.

The Texas Towers were the brainchild of the United States military in the 1950s. Fixated on the possibility that the Soviet Union would attack by air, we therefore needed as much advance warning as possible. And so:

Build five facilities offshore, string them along the Northeast, equip them with radar, provide constant manned surveillance.

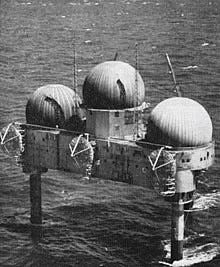

These towers were triangular islands, 200 feet per side, rising nearly 100 feet above the sea, each perched on three huge legs; 6000 tons of steel needed to make one tower. As many as 100 people served and slept onboard.

The first to become fully operational, in 1958, was called Texas Towers #2, 110 miles east of Cape Cod, controlled from the North Truro Air Force Station (now Highland Center in Cape Cod National Seashore). Numbers 3 and 4 were constructed on Nantucket Shoals and off New Jersey. Numbers 1 and 5, meant to be farther north, never materialized — for good reasons.

From the moment they were erected, using building practices developed for oil drilling platforms off Texas (hence the name), these towers never seemed right. They rolled and pitched so much that even seasoned officers became seasick. Howling winds, creaking and groaning decks and machinery made it hard or impossible to sleep. One of the world’s largest foghorns sounded every 29 seconds when weather called for it, which sometimes meant 24 hours a day, days at a time.

Among those serving tortuous shifts, the towers earned a nickname: “The Iron Bastards.”

As a story in Life Magazine recounted, a man on #2 was in the mess hall, the tower pitching so badly it felt like they were jogging. Not able to take it anymore (but having no choice), he stood up and yelled, “Go ahead, you monster! Walk yourself all the way back to Provincetown.”

Within just a few years the whole point of these towers, to provide early warning from Russian attack, was rendered moot: New intercontinental ballistic missiles could travel 15,000 miles an hour. The early warning a perfectly functioning Texas Tower could provide was, maybe, a few seconds.

Yet the towers remained. The investment was too great to just abandon them, not to mention admitting lunacy.

Texas Tower #4 was even more problematic than #2, in deeper water at 185 feet, constantly rolling and groaning. When Hurricane Donna inflicted serious damage in September, 1960, most of the crew offloaded but 28 remained; the military worried that if the site was abandoned, the Russians would come aboard and ferret out technological secrets.

Madness turned murderous three months later, January, 1961, when another storm struck. The tower sank, all 28 men killed, only two bodies ever found.

Finally the towers were consigned to the watery equivalent of mothballing. The plan was to salvage #2, get the steel onto land, but even that didn’t work; the tower sank and remains at the bottom to this day. Deadly #4 also sits in a watery grave. #3 was knocked off its legs, filled with foam, and floated to shore.

This might sound like a stupid sci-fi horror pic, but no, it’s history.

One takeaway is to see these towers as an expression of mass hysteria, collective delusion or paranoia.

Then there’s hubris; overweening certainty, expressed generation after generation, that humans can control and dominate Nature, even the Atlantic Ocean, with engineering, steel, and technology.

As we face the prospect of industrializing these waters in the name of renewable energy (or fossil fuel), let’s acknowledge hubris as the ageless common denominator, which is why this cautionary tale — but not the towers — deserves resurrection.

Haven’t subscribed yet? With all due respect, why not? Make it possible to see a Voice and support good reporting, strong perspectives, unique Cape Cod takes every week. All that for far less than a cup of coffee. Please subscribe:

https://sethrolbein.substack.com/welcome

And if you are into Instagram, want to see some additional material, maybe share the work, here you go:

Thanks for this. When I was maybe 7 or 8, my father was gone for months "working on the Texas tower". I was an adult before I learned they weren't in Texas. Finally I know what exactly they were meant to be.

https://www.hsoy.org/blog/2023/12/9/barnstables-forgotten-dude-ranch

Hey Seth! This is a cool bit of local history. It even includes waterskiing with HORSES!

It's from the archives of the Historical Society of Old Yarmouth. Don't know if you might be able to repurpose this for one of your own articles.

Dave Doolittle